Out on the horizon of agriculture’s future, an army 40,000 strong is marching towards a shimmering goal. They see the potential for a global food system where pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers are but relics of a faded age.

They are not farmers, but they are working in the name of farmers everywhere. Under their white lab coats their hearts beat with a mission to unlock the secrets of the soil — making the work of farmers a little lighter, increasing the productivity of every field and reducing the costly inputs that stretch farmers’ profits as thin as a wire.

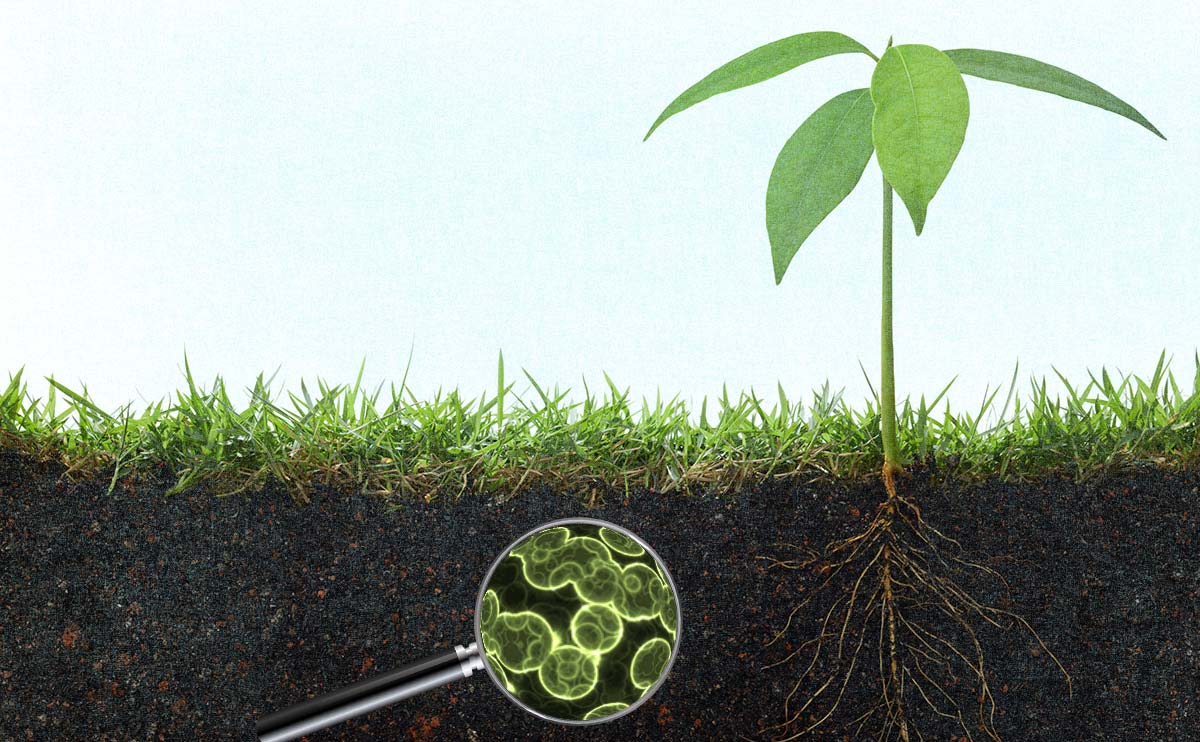

‘Producing more food with fewer resources may seem too good to be true, but the world’s farmers have trillions of potential partners that can help achieve that ambitious goal. Those partners are microbes.’

The American Society of Microbiologists (ASM) recently released a treasure trove of their latest research and is eager to get it into the hands of farmers. Acknowledging that farmers will need to produce 70 to 100 percent more food to feed the projected 9 billion humans that will inhabit the earth by 2050, they remain refreshingly optimistic in their work. The introduction to their latest report states:

“Producing more food with fewer resources may seem too good to be true, but the world’s farmers have trillions of potential partners that can help achieve that ambitious goal. Those partners are microbes.”

Mingling with Microbes

Linda Kinkel of the University of Minnesota’s Department of Plant Pathology was one of the delegates at ASM’s colloquium in December 2012, where innovators from science, agribusiness and the USDA spent two days sharing their research and discussing solutions to the most pressing problems in agriculture.

“We understand only a fraction of what microbes do to aid in plant growth,” she says. “But the technical capacity to categorize the vast unknown community [of microorganisms] has improved rapidly in the last couple of years.”

Microbiologists have thoroughly documented instances where bacteria, fungi, nematodes — even viruses — have formed mutually beneficial associations with food plants, improving their ability to absorb nutrients and resist drought, disease and pests. Microbes can enable plants to better tolerate extreme temperature fluctuations, saline soils and other challenges of a changing climate. There is even evidence that microbes contribute to the finely-tuned flavors of top-quality produce, a phenomenon observed in strawberries in particular.

“But we’re only at the tip of the iceberg,” says Kinkel.

via Microbes Will Feed the World, or Why Real Farmers Grow Soil, Not Crops – Modern Farmer.