Hawaii imports 90 percent of what it eats at great environmental cost. Now ag activists seek to make ‘grown here, not flown here’ a reality.

HONOLULU—When my Airbus touched down at Honolulu International Airport, I was one of 30,843 people to arrive in Hawaii on a June day. As a crush of tourists mobbed rental car counters and taxi stands, massive container ships steamed into the Port of Honolulu just across the harbor, carrying some of the 6 million pounds of food shipped to Hawaii every day to feed the state’s 1.4 million residents and 8 million annual visitors. On nearby runaways, cargo planes landed packed with fresh fruit and other perishable items that wouldn’t survive the 2,500-mile ocean voyage. The world’s most isolated chain of islands, Hawaii imports nearly 90 percent of its food at a cost of more than $3 billion a year.

There’s a high environmental price to be paid for relying on a 747 or 40,000-ton ship as your food truck. The largest cargo vessels can emit as much pollution as 50 million cars in a year, according to a 2009 study, and shipping accounts for about 4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Just consider the carbon footprint of putting a Hawaiian steak on local plates: Tens of thousands of calves are raised on the Big Island of Hawaii every year and then loaded on barges to the mainland. There they’re fattened, slaughtered, shrink-wrapped, and shipped back across the Pacific to the islands. Meanwhile, pests and parasites that hitch a ride on this nonstop caravan of cargo ships are decimating Hawaiian wildlife, forests, and farm fields at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

But if the status quo is bad, what happens if the ships stop coming could be far worse.

“I think there’s a sense here in Hawaii that if we have a hurricane or a tsunami, how long could we last with our food supply?” said Jenai Wall, chief executive of Foodland, Hawaii’s largest supermarket chain, which relies on imports for about 80 percent of its sales. She paused. “Not very long.

”Probably less than a week, actually.“If something catastrophic happened on the mainland, we’d have about three days of food in the stores,” said Una Greenaway, a farmer on the Big Island. “We’re very, very food insecure here, but we don’t have to be.

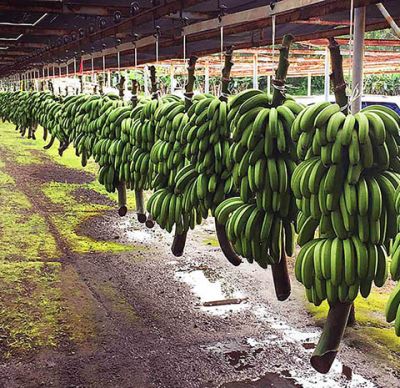

”Greenaway, who grows coffee, cacao, apples, bananas, and pineapples on a five-acre farm, is part of burgeoning local food movement in Hawaii that’s attempting to reverse decades of deepening dependence on imports. In recent years, there’s been a flowering of farms, farmers markets, and eat-local campaigns across the islands. Not all that different, in other words, from what’s going on in the crunchier parts of the mainland. But this is no foodie fad. It’s state policy. As globalization and climate change upend worldwide food production, Hawaii is moving to foster homegrown agriculture in a way that could be a model for others. One key: kicking the state’s severe addiction to another carbon-intensive import—oil.

Source: Food Independence Could Be a Matter of Survival for the U.S.’ Most Isolated State | TakePart