On April 1, California Governor Jerry Brown stood in a field in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, beige grass stretching out across an area that should have been covered with five feet of snow. The Sierra’s snowpack — the frozen well that feeds California’s reservoirs and supplies a third of its water — was just eight percent of its yearly average. That’s a historic low for a state that has become accustomed to breaking drought records.

In the middle of the snowless field, Brown took an unprecedented step, mandating that urban agencies curtail their water use by 25 percent, a move that would save some 500 billion gallons of water by February of 2016 — a seemingly huge amount, until you consider that California’s almond industry, for example, uses more than twice that much water annually. Yet Brown’s mandatory cuts did not touch the state’s agriculture industry.

Agriculture requires water, and large-scale agriculture, like that in California, requires large amounts of water. So when Governor Brown came under fire for exempting farmers from the mandatory cuts — farmers use 80 percent of the state’s available water — he was unmoved.

“They’re not watering their lawn or taking long showers,” he told ABC’s “The Week” the Sunday after he announced the restrictions. “They’re providing most of the fruits and vegetables of America to a significant part of the world.”

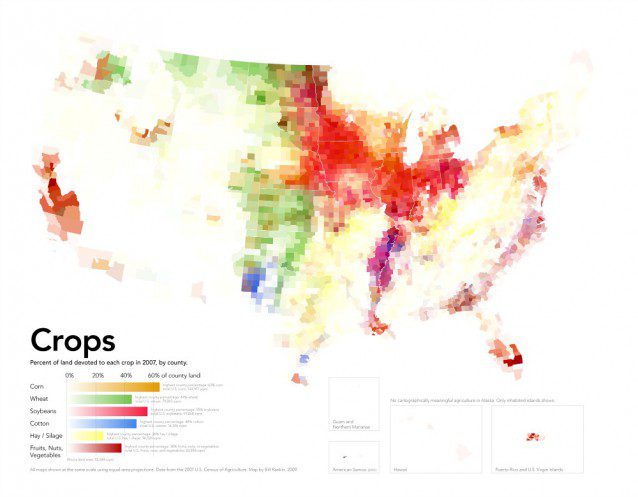

Almonds get a lot of the attention when it comes to California’s agriculture and water, but the state is responsible for a dizzying diversity of produce. Eaten a salad recently? Odds are the lettuce, carrots, and celery came from California. Have a soft spot for stone fruit? California produces 84 percent of the country’s fresh peaches and 94 percent of the country’s fresh plums. It produces 99 percent of the artichokes grown in the United States, and 94 percent of the broccoli. As spring begins to creep in, almost half of asparagus will come from California.

“California is running through its water supply because, for complicated historical and climatological reasons, it has taken on the burden of feeding the rest of the country,” Steven Johnson wrote in Medium, pointing out that California’s water problems are actually a national problem — for better or for worse, the trillions of gallons of water California agriculture uses annually is the price we all pay for supermarket produce aisles stocked with fruits and vegetables.

Up to this point, feats of engineering and underground aquifers have made the drought somewhat bearable for California’s farmers. But if dry conditions become the new normal, how much longer can — and should — California’s fields feed the country? And if they can no longer do so, what should the rest of the country do?

“It’s Not Just A California Drought Problem, It’s A Problem With Our Whole Food System”

In 2014, some 500,000 acres of farmland lay fallow in California, costing the state’s agriculture industry $1.5 billion in revenue and 17,000 seasonal and part time jobs. Experts believe the total acreage of fallowed farmland could double in 2015 — and that news has people across the country thinking about food security.

“When you look at the California drought maps, it’s a scary thing,” Craig Chase, who leads the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture’s Marketing and Food Systems Initiative at Iowa State University, told ThinkProgress. “We’re all wondering where the food that we want to eat is going to come from. Is it going to come from another state inside the U.S.? Is it going to come from abroad? Or are we going to grow it ourselves? That’s the question that we need to start asking ourselves.”

The California Central Valley, which stretches 450 miles between the Sierra Nevadas and the California Coast Range, might be the single most productive tract of land in the world. From its soil springs 230 varieties of crops so diverse that their places of botanical origin range from Southeast Asia to Mexico. It produces two thirds of the nation’s produce, and, like Atlas with an almond on his back, 80 percent of the world’s almonds. If you’ve eaten anything made with canned tomatoes, there’s a 94 percent chance that they were planted and picked in the Central Valley.

Source: California’s Drought Could Upend America’s Entire Food System | ThinkProgress